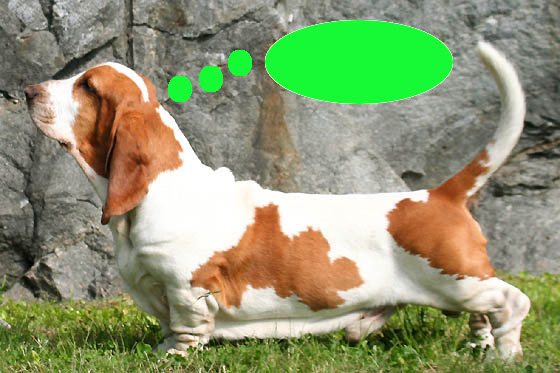

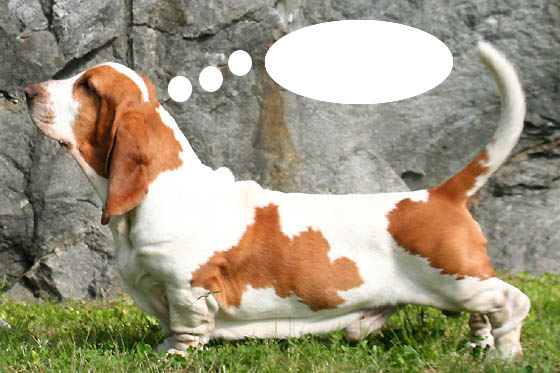

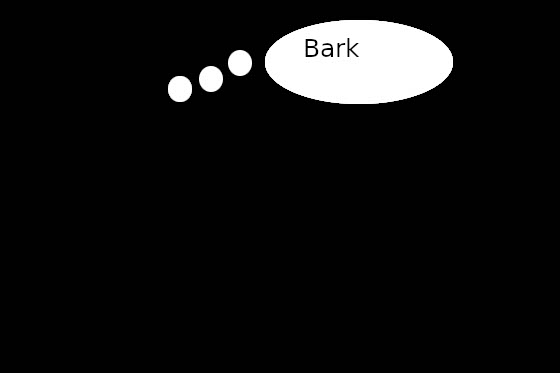

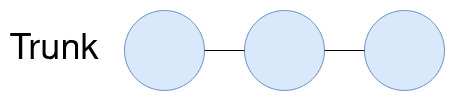

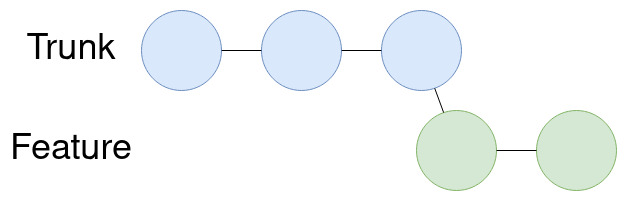

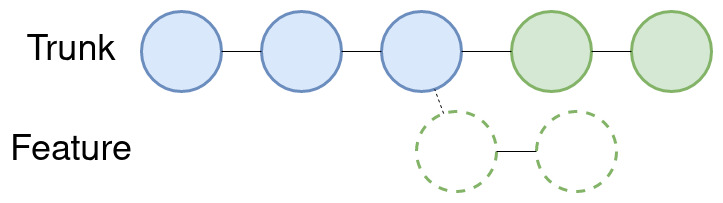

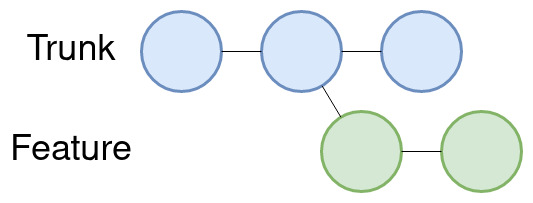

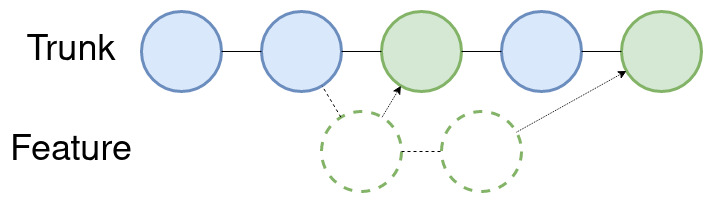

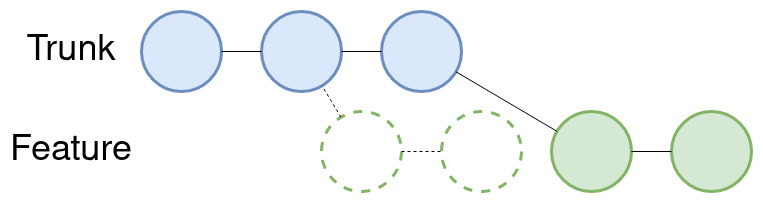

class: center, middle # git ## From the git go ### (An Introduction to git) --- # Agenda - Disclaimers - What is Git? - Version Control Systems - Why Use Git? - Git Web Interfaces - Common Git Operations, described ??? What we're going to try to get through in the next 45 minutes or so. We'll start with a couple of clarifying remarks about this presentation itself then move on to discussion about what _precisely_ git is After we figure out what git is we'll move onto **why** you should use it And after that we'll briefly discuss some interfaces for git, and some common git operations --- ## Disclaimers What This Presentation... .cols[ .col40[ **Is** - An high level, conceptual introduction to what git is - A brief explanation of what git does, and how it does it - A introduction to why you might use git - A very brief walkthrough of some common git operations ] .col10[] .col40[ **Is Not** - Exhaustive - A git labratory/tutorial - A nuanced discussion of all git operations - A nuanced discussion of all git workflows - A git troubleshooting guide - A comparison of git to other version management tools - A walkthrough of git web interfaces ] ] ??? This presentation is meant to be an introduction to to the concepts behind git. It contains far more pictures, diagrams, and explanation than it does instruction about what to type into your terminal window when. It contains more commentary on the commonalities shared between all the ways of using git, rather than opinions, suggestions, or instruction on specific ways of using git. This presentation _probably_ isn't enough, on its own, for you to begin confidently using git yourself, but I hope it _is_ enough to familarize you with the git's functionalities, and give you a leg up when you dive into actual git usage. --- # What is Git? > Git is a distributed version-control system for tracking changes in source code during software development. It is designed for coordinating work among programmers, but it can be used to track changes in any set of files. Its goals include speed, data integrity, and support for distributed, non-linear workflows. - Wikipedia .footnote[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Git] ??? So - what is git? -- # TL;DR ??? That's a lot of text. Let's boil it down a bit. --- class: center, middle # Git is a **version control system** ??? Much better. Git is a version control system, so... --- # Version Control Systems What is a version control system? ??? What's a version control system anyways? -- Let's agree on some terminology. ??? In order to answer that we're going to need to be able to speak the same language -- **Note that this terminology is for the purposes for this presentation, and _is not_ a part of standard git terminology.** ??? A quick note here - we're going to use some terms that **I've** generalized here, for the sake of speaking generally before we zero in on git specifically. We'll come back around to the more "git specific" widely recognized terms for some of these things a bit later in the presentation, when we start talking about git specifically. -- - **Versionable** - Something there can be multiple versions of. - Idea/Concept/etc ??? A versionable is a thing that you can have versions of. It's more of an idea rather than anything you can touch, or read, or deliver. There may eventually be a _final_ version of it (or there might not) - but no individual version is the versionable --- class: center, middle Hypercube / Versionable  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypercube#/media/File:8-cell.gif ??? Think of the versionable like a hypercube Something you can conceptualize - but can't quite be concretely pinned down in three dimensions. --- # Version Control Systems What is a version control system? Let's agree on some terminology. **Note that this terminology is for the purposes for this presentation, and _is not_ a part of standard git terminology.** - **Versionable** - Something there can be multiple versions of. - Idea/Concept/etc - **Version** - A concrete representation of a versionable - v1, v2, current, final, 1.3.4, etc ??? Versions are the concrete manifestations of the versionable. There will probably be multiple of them over time, and they probably have some kind of relation to one another None of them _are_ the versionable, but they all represent it. -- - **Diff** (differential) or Delta - The differences between any two given versions ??? And finally the diff (short for differences, or differential), sometimes called a "delta" depending on the field you're in. Diffs are a record of the differences between any two given versions. The "tracked changes", so to speak. As people we tend to focus on the _versions_ but diffs are an integral part of version control systems. --- # Diffs Diffs represent change between two versions so they must have... - A way to locate changes within the version - A way to represent changes within the version ---- .cols[ .col40[ Diffs can operate on different metrics depending on what makes them useful - Bytes - Characters - Pixels - Lines - Sentences - Paragraphs - etc ] .col10[] .col40[ How different "diffing" algorithms accomplish locating and representing changes is an interesting (and non-trivial) problem to solve, which is often informed by the context the algorithm will be used in. These complexities are beyond the scope of this presentation. ] ] ??? Diffs have some special properties when it comes to version control systems. They absolute must have... - A way to locate changes within a version (and) - A way to represent changes within a version Depending on what your versionable is, and what your versions are, it may be desirable for your diffs to have different "granularities" - ranging from bytes to paragraphs. Ultimately the granularity of your diff should be informed by what makes the diff - useful (and) - deterministic There are quite a few interesting diffing algorithms around which serve different purposes, but that falls a bit outside the scope of this presentation. --- class: center, middle ## **Diffs are the crux of most modern full featured version control systems** ??? As it turns out _diffs_ (rather than _versions_) are the crux of most modern version control systems -- So how about some examples? ??? Let's walk through some examples of why this is the case --- # Version 0 ??? Here, from the perspective of most version control systems, is the first version of just about everything -- .center[.middle[... it's blank]] ??? Nothing Why? --- # Diff #1 .center[] ??? Because adding something is the first diff --- # Version 1 .center[] .footnote[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basset_Hound#/media/File:BassetHound_profil.jpg] ??? Here's version 1 of our versionable (the blank canvas was 0 indexed) A quick note - in both the previous example and all the examples going forward the "diff" is signified by the green tinged elements --- # Diff #2 .center[] ??? This is our first "regular" diff - it isn't the one which adds the original content, but instead makes an incremental change to the version that exists already. --- # Version 2 .center[] ??? And here's the version which results from apply that diff to our previous version. Let me just take a moment here to say I am not the most gifted Photoshopper, so in case it is unclear we've added a thought bubble, so we can know what this pup is thinking. --- # Diff #3 .center[] ??? And this final diff reveals the profound thoughts he's having at the moment. --- # Version #3 .center[] ??? Here's the "final version" --- class: center, middle This makes logical sense to us, but version control systems (usually) only care about the diffs, and dynamically reassemble the "version" - so we can do some interesting stuff. ??? Walking through things this way makes logical sense to us (which is to say, humans rather than machines) But most version control systems would store either **only** version 0, or **only** version 3, they would however maintain all of the diffs. This allows the VCS to dynamically recreate versions for us (by "replaying" diffs only up to a certain point) and the minimal nature of the diffs allows us to potentially do some interesting stuff. --- # Diff 2 + Diff 3 .center[] ??? For example - here are diffs 2 and 3 replayed over version 0. As you can see these diffs are able to be replayed over a different starting point and still produce a readable image, but it is very different from our original "final" version. --- # Diff 1 + Diff 3 .center[] ??? Here are diffs 1 and 3 replayed over version 0. Again, valid, but resulting in a different end state. --- class: center, middle Note that the fact that version control tools only care about diffs occasionally causes trip-ups. For example, if we introduce a new diff that looks like... ??? This focus on _diffs_ rather than versions can be a cause of headaches when you are first using git For example, lets take a look at this new diff... --- # Diff A .center[] ??? Pretty simple, right? Ignore the black background here - it's just meant to make the green easier to see. --- class: center, middle and we try to apply it to Version 3 we get... ??? If we try to apply this to our old version 3 we get... --- .center[] .center[A very confused pup] ??? A very confused pup But - if we were to apply this to version 2 we'd just get a dog saying "woof" instead of "bark" - right? --- class: center, middle Depending on our version control tool this might not be allowed to happen. Ie: No version can have diff #3 and diff A in its history. In git this would cause what is known as a "merge conflict" if we tried to put both of those diffs in the history of the same version. ??? Errors like this are going to be representative of cases where your diffing algorithm can't determine what exactly you expected the final product to look like - and so it will ask for your input in applying the diff. In git parlance this is a "merge conflict" and is the bane of my new git users. Hopefully, armed with the deeper understanding of what git is actually _doing_ that this presentation is meant to provide you with you'lll experience fewer of these in the future. Though keep in mind that some merge conflicts are 100% unavoidable --- class: center, middle # A Quick Disclaimer These examples are meant only to demonstrate the basics of diffs - displaying diffs using images breaks down rather quickly in more complex scenarios. ??? Just a quick little disclaimer about those examples - In them we used images to represent diffs and versions, and used what would be considered an exceptionally simple diffing algorithm. This examples break down in more complex cases - you may be able to think of a few already. This analogy is useful for visualing _simple_ diffs - but in order to model more complex scenarios we'd need the real deal. --- # Version Control Systems Version control systems come in two primary flavors ??? Alright - so now that we've got a firm understanding of diffs we can move onto some of the more complex, but pivotal, attributes of version control systems. First up, VCSs come in two different flavors -- - Forward Differential - Keep the original version, track diffs to dynamically rebuild future versions - Backward Differential - Keep the current version, track diffs to dynamically rebuild past versions ??? Forward differential systems - where you move _forwards_ from version 0 applying diffs to dynamically generate all other versions and Backward or reverse differential systems - where you move _backwards_ from the latest version applying diffs in "reverse" to dynamically all previous versions -- Both of these are facilitated by the fact that... Given v1 and d1: `d1(v1) -> v2` (Forward diff) Given v2 and d1: `-d1(v2) -> v1` (Backwards diff) ??? We can right this out as a kind of math-y looking thing like this. Basically, in a forward diff system you apply diff #1 to version #1 to get version #2 In a reverse diff system you apply the inverse of diff version 1 to version #2 to get version #1 -- These are extensible to any number of diffs Given v1 and d1..dn: `dn(dn-1(dn-2(...(d1(v1))))) -> vn` Given vn and dn..d1: `-d1(...(-dn-2(-dn-1(-dn(vn))))) -> v1` Advanced version control systems (eg: git) may use a mixture of these two approaches. ??? Importantly you can apply these diffs, in whatever direction your VCS uses, in series in order to generate any of N different versions. If you read these expanded pseudo-functions from the inside out you can see they are just expanded versions of the simpler pseudo-functions we started with. One more tangential note: In real VCSs, where concerns about speed, size, etc are factors, rather than just mathematical purity, you'll often see a combination of _both_ of these methodologies. I'll leave sensibly combining them as an excersize for the reader. --- # From VCS's to git Now that we understand how version control systems work in the abstract we can move on to understanding how git works. In git the "versionable" is a group of files arranged in a hierarchy. (A directory structure) Git calls the versionable a "repository". A "version" is files on disk. Diff's have a "granularity" down to a single **line** of plaintext. This means git is well suited to manage plaintext source code, but diffs _mostly_ lose their meaning when used to track things like... ??? **Whew** Alright - with all that out of the way I'd say we've established a pretty good baseline understanding of version control systems in the abstract. Let's talk about git in particular now. We can pretty much map our previous concepts 1:1 onto things in git: - The "versionable" in git is often called a "repository" - it's pretty much a directory with files and subdirectories. - A "version" of that versionable is just some arrangement of files in that directory structure, with some content in those files - Diffs can operate on changes down to a single line of plaintext With these considerations in mind it follows that git is well suited to manage **source code**, but diffs start to look a little strange if you think about... --- class: middle .cols[ .col40[ - Binary files - Compiled/minified plaintext files - Prose - Unless you're using markdown and something like [semantic line breaks](https://sembr.org/) ] .col10[] .col40[ - Images - Non-deterministially generated files - Anything not represented by plaintext ] ] Git _can_ track these files - but the diffs will be meaningless, and large files may cause performance issues. ??? Any of these. To clarify git **can** track these files, but diffs will be mostly meaningless, and it isn't explicitly designed to work great when tracking them. This can impact usability/readability/git performance. --- # From VCS's to git - Commits Git wraps diffs in a containing structure known as a "commit". Commits are the basic working unit in git. Commits contain... .cols[ .col40[ - a diff - a unique identifier - a timestamp - Authorial information - A commit message - A list of effected files - Some additional metadata ] .col10[] .col40[ Note that diffs are _minimal_, which is to say that they only effect changed lines, and only reference enough of the file to locate and change the changed lines. This means when working with larger files changes encapsulated in multiple different commits may be able to be applied against files in various orders, so long as they don't conflict. ] ] ??? Most of the time instead of discussing "diffs" when it comes to git you'll instead be discussing "commits" "Commits" are a kind of containing structure that git wraps around diffs in order to inject some more information into them and make them more easily addressable for when you want to start manipulating them. Commits include the diff, but also other stuff like some some authorial information, a unique id, a message, and other goodies. An import note here is that much like how the diffs in our previous example only changed certain sections of the image they were applied to, commits are "minimal" in what they change. They aren't _explicitly_ linked to the version on each side of them. They only require enough of the previous version to exist to locate and apply the changes they contain - and can be moved around independently otherwise. --- # From Diffs to Commits So what does this look like when applied to a file in the real world? .cols[ .col40[ README.md (version 1) ```markdown Example Project! A brief explanation ``` ---- README.md (version 2) ```markdown Example Project! A kind of brief explanation More in depth explanation ``` ] .col10[] .col40[ Diff (v1 -> v2) ```diff --- a/README.md +++ b/README.md @@ -1,3 +1,5 @@ Example Project! -A brief explanation +A kind of brief explanation + +More in depth explanation ``` ] ] ??? Let's take a look at our first real world example. Here we have simple README file. We started with a _very_ minimal README, with one line of explanation. In the following version we provide _200%_ more explanation! Here our diff, based on changed on added lines, includes green for additions (like we're used to seeing) and red for removed content. Note that though we only kind of changed the first line of the README we still changed the line, and so git rewrites it. --- # From Diffs to Commits And the commit message (from `git log -p`) ```diff commit a50a1eb59117a11366c1da57018501c1a96275b7 (HEAD -> master) Author: Brian Balsamo <Brian@BrianBalsamo.com> Date: Thu Aug 13 21:13:00 2020 -0500 Expanding the README This commit adds more explanation to the project's README. diff --git a/README.md b/README.md index 1eccec1..690e6a3 100644 --- a/README.md +++ b/README.md @@ -1,3 +1,5 @@ # Example Project! -A brief explanation +A kind of brief explanation + +More in depth explanation ``` ??? And here we have the actual commit message. We can see that it contains the diff as well as that other information we discussed. You can see... - That long ugly mishmash of numbers and letters that is the commits unique id - My name and email - The date and time the commit was made - The message that narratively explains the contents of the commit - You may noticec I kind of repeat myself there. a _lot_ of systems use the first line of a commit message (if its followed by a blank line) as the "title" of a pull request that contains only a single commit, so its a good habit to get into to make that first line short and readable, and repeat it in your first sentence in the message itself. --- # from VCS's to git - Branches Up until now we've looked at strictly "linear" versions. v1 -> v2 -> v3 -> etc This is seldom how real projects look once they reach a certain amount of complexity, or involve multiple people. Git (and most other version control systems) allow for the creation of multiple different "branches" Git branches are simply ordered lists of commits, which are evaluated in order to produce a version of the directory under version control. In this way a branch can act as the "history" of a given version of the versionable. Branches can be branched _from_ other branches - meaning that those branches will share a history up to a given commit before diverging. Branches can be **merged**, which will combine the history of one branch with another's. ??? So, with all of that said we understand commits pretty well now, but there is one big caveat: We've only been dealing with very linear sets of diffs/versions, with version 2 following version 1, etc. I don't know about you folks, but I don't think I've _ever_ been on a project that is reasonably complex or long running which _actually_ follows this nice linear path. Luckily, git accounts for this with a simple but powerful concept: **Branches** Branches are just an ordered list of commits which, when evaluated, produce a version. So in our simple case, our _only_ branch would be commit 1, followed by commit 2, etc. But branches give us the ability to... - have variations of these lists of commits - partially share histories between them - track the relationships between these branches easily - (and) combine them later if we so choose Branches are also an easily addressable part of the version control system, so a lot of git operations (which we'll get to) use them as an easy way to address groups of commits. --- # from VCS's to git - Branches Branches are a powerful tool that... - Establish explicit relationships between (potentially many) different versions of the code - Make reasoning about the relationships between different versions of the code much easier - Allow multiple features to be developed in parallel without interferring with each other - Allow multiple people to develop in parallel without stepping on each other's toes - Facilitate sequestering experiments from the stable code In combination with automation tooling or agreed upon workflows branches can also - Formalize the method by which code enters the stable branch - Provide targets that automation solutions can address - Provide insight into ongoing work ??? Branches buy us a lot when it comes to git - They establish explicit relationships between versions of the code - They make reasoning about those different versions easier - They allow paralle work to be completed - Both different features being work on at the same time, and different people working in parallel - They keep our "stable" code safe from code in development, or experiments Branches also provide an excellent organization unit to leverage when combined with agreed on workflows or automation solutions Let's take a look at some examples... --- # Branches - Examples .center[] .center[A single branch] ??? Here we have a simple branch with three commits on it. Not the most interesting - but now we know how we can represent branches and commits in diagram form. --- # Branches - Examples .center[] .center[Trunk Branch + Feature Branch] ??? Here we have a pretty basic example of the most common use of branches. We have our stable code in the trunk branch and we're building a new feature in a "feature branch" --- # Branches - Examples .center[] .center[Merged Feature Branch] ??? And here we have what the branch would look like after we merge that feature branch into our trunk branch. This example is pretty basic - note that it is basically just our linear version history with the added benefit of sequestering the code we're developing until we're ready to release it. --- # Branches - Examples .center[] .center[A slightly more complex feature branch case] ??? This example is a little more complex. As you can see - we started developing a feature but other stuff happened on the trunk branch in the interim. So what exactly is going to happen here when we go to merge this feature into our trunk branch? --- # Branches - Examples .center[] .center[Merged Feature Branch] ??? In actuality git is going to do something a little more complex than this (it's going to create a merge commit) but functionally after we merge this branch into the trunk branch is what you see here. We've taken that work in our feature branch and interleaved into the trunk branch in the order the commits actually occurred. It's important to note this is the first (real) scenario we've seen where a merge conflict _could_ occur. If the commit that previous existed in the trunk branch can't be applied after the first change in your feature branch -> Boom If the second commit in the feature branch can't be applied after the commit that existed in the trunk branch -> Boom Note that these merge conflicts must be remedied in the history of the trunk branch, and prevent the trunk branch from being in a good state on the person doing the merge's machine until the merge conflicts are remedied. --- # Branches - Examples .center[] .center[Rebased Feature Branch] ??? An alternative to merging that feature branch straight away, which makes it impossible for anyone to have a broken trunk branch is known as rebasing Note that rebasing is a **VERY** powerful operation in git, but also one of the few operations that can be **destructive**, because it rewrites history. I'd have included a picture of a the back to the future Dolorean here if I would have found one I was sure of the rights for :) Rebasing a branch essentially moves that branch forwards to the tip of the branch that it originated from by replaying the commits from a new starting point, as we can see in this diagram. Note that we can still get merge conflicts (for the exact same reasons as the previous example) but these merge conflicts are safely tucked away... 1) In the rebase operation 2) In the feature branch, rather than the trunk branch --- class: middle, center # Why Use Git? ??? Alright - so now we understand version control systems generally and git in particular We've seen _how_ git accomplishes what it accomplishes, but _why_ should you use git? --- .cols[ .col40[ ### How Do These Relate to Each Other? ### What Was Changed in Them? - projv1.doc - projv2.doc - projv2.1.doc - proj_final.doc - proj_final2.doc - proj_3_brianedits.doc - proj_3_2_final.doc - projectv4_final_final.doc - proj4_final2.doc - proj3_SEND_TO_CLIENT.docx - proj_2_new_internal.docx ] .col10[] .col40[ ### Where _is_ the final version of that? - Email - Teams - Dropbox - Company File Storage - Team Member #1's Desktop - Team Member #2's Desktop ---- ### Git keeps everything organized, explicit, and easily discoverable. ] ] ??? Everyone has one of these directories hidden somewhere in the deep dark recesses of their inbox or Documents folder. No one likes them, they cause problems, and in comparison to everything we've gone over I hope everyone agrees that throwing "v1" or "v2.5" in a file name is pretty much living in the stone age. Git is going to keep track of what changed, why it changed, and how it changed more explicitly than any other tool that isn't an alternative full featured VCS. Additionally, once you agree to keep everything in a git repository it _stays in the git repository_. It becomes impossible to spread versions out through multiple mediums. --- class: middle, center # You **will** break your code. Git keeps that working version safe in the history. ??? Everyone has done it - you sit down with code the works intending to add a feature, fix a bug, or improve something, and 20 minutes you have a mess. Git makes it so you can easily figure out what you've changed since the code last worked, file by file, and line by line, and if required revert those changes. --- class: middle, center # You won't be cowbody coding forever (probably) Git facilitates working with others, and on different features in parallel ??? You may think at the start of a project: "I don't need to use git, I know my code! I'll just remember why I changed what I changed and how I changed it!" And that may work fine right up until the point... - You forget something - Someone joins your team - Someone asks you to work on two things at oncef - Someone changes a priority while you're working on the previous one Git makes all of these things a non-issue. --- class: middle, center # You're going to want automation The structure, organization, and metadata git provides make it an ideal centerpiece for your DevOps pipeline. ??? Git makes an _excellent_ backbone for automation. It exposes **tons** of data to automation tooling, gives them tons of insight into the code, and it gives them the ability to react to changes or even make their own changes to the code. --- class: middle, center # You'll have to debug something eventually Git contains the history of every line in the repository. Reading an opaque function in the source? See what the commit that introduced it was related to. ??? Everyone makes mistakes When you make mistakes while programming you have to debug them. Eventually a mistake will slip by for a while, and you'll have to debug it in the future. Git's explicit handling of the project history in combination with the ability to fill it with relevant metadata makes it an excellent tool for understanding what happened in the past and why - so that that on down the road if something is broken, at least it's possible to understand _why_ it existed in the first place, and maybe what played into its broken implementation. --- class: middle, center # Eventually you'll need to support more than one version ??? This is an absolute nightmare without something like git to rely on for keeping versions and version histories in line. --- # Common Git Operations - `git init [directory]`: Mark [directory] as the versionable - `git clone`: Retrieve and existing versionable - `git add [file]`: Add a file to the versionable, or add its diff to the commit - `git commit`: Create a commit from the `add`ed files - `git branch [branch-name]`: Create a new branch named [branch-name] off of the current commit - `git checkout [branch-name]`: Switch to working in [branch-name] - `git merge [branch-name]`: Merge [branch-name] into the branch you are currently in - `git rebase [branch-name]`: Rebase the branch you are currently in onto [branch-name] ??? Alright - so now we understand what git is, how it works under the hood, and why we should use it. But how _exactly_ do we go about using it? git itself is a simple command line utility with some very powerful and configurable commands. Here are the basics you should know: - git init [directory]: Mark [directory] as the versionable - git clone: Retrieve and existing versionable - git add [file]: Add a file to the versionable, or add its diff to the commit - git commit: Create a commit from the added files in the branch you're currently in - git branch [branch-name]: Create a new branch named [branch-name] off of the current commit - git checkout [branch-name]: Switch to working in [branch-name] - git merge [branch-name]: Merge [branch-name] into the branch you are currently in - git rebase [branch-name]: Rebase the branch you are currently in onto [branch-name] --- class: middle, center # Git Navigation ## [Live "Coding"!](https://learngitbranching.js.org/?NODEMO) ??? You'll notice a few of the commands we just went over have to do with navigating the git tree and others are based on "what branch you're currently in" Navigating git is one of the key skills to master when you get around to actually _using_ git To that end, I've found a nice little site that allows you visually navigate a git tree while displaying it for you. Let's demo some basic git navigation... ---- - Basic feature branch - Demo with fast foward - Demo with --no-ff - Feature branch + change in master - Note that you _can't_ fast foward here - Feature branch + change in master + rebase - Git Flow --- # Git Web Interfaces There are a variety of web interfaces which sit on top of git. These web interfaces frequently provide additional functionalities which synergize well with git: - Pull Requests - Issue Trackers - Planning Tools - Wiki's - Integration with CI/CD - Artifact Storage ??? Note that though we don't have the time to go into them in this talk there are a variety of web interfaces for git which facilitate collaboration. They often contain _very_ handy tools which many people will talk about interchangably with the core git functionality Things like Pull Requests are absolute integral to most real world git workflows. A pull request is when you announce that you'd _like_ to merge one branch into another, and invite others to review what changes that merge would make. "Merging a pull request" then performs the branch merge. --- # Git Web Interfaces ### [GitHub](https://github.com/) - Recently acquired by Microsoft ### [GitLab](https://about.gitlab.com/) - [Currently](https://about.gitlab.com/handbook/being-a-public-company/) a private company ### [BitBucket](https://bitbucket.org/product) - Part of the [Atlassian](https://www.atlassian.com/) suite ??? Here three of the most common providers of git web interfaces. Of note, most cloud service providers also provide some sort of git web interface which is integrated to the rest of their service offerings - AWS - Azure (though GitHub is moving into this space, after the acquisition) - GCE --- # Glaring omissions ## What to research next - The git CLI - We went over some basics of git navigation, but the git CLI is a veritable swiss army knife of functionality! - git GUI clients - Git Workflows, in depth - Github Flow - GitFlow - Using git with remote repositories - This is a biggie we omitted that you'll _probably_ see in your first more detailed "using git" tutorial ??? Just as a heads up, this presentation has a few glaring omissions in it - It doesn't go over the git CLI in _nearly_ enough depth. - Luckily, there are plenty of other materials that go over this interface - It doesn't go over and git GUI clients, which you may prefer using over the CLI - It _barely_ touches on some common git workflows, which themselves are often important to understand in order to use git with a team - It _completely omits_ the distributed nature of git and working with remotes. - This is probably the biggest omission, but all of the basics we covered still apply, there are just some extra steps --- class: middle .center[**Thank you**] .center[Questions?] .center[Brian Balsamo] .center[brian@brianbalsamo.com]